Montana IPM Bulletin, Fall 2014

The Montana IPM Bulletin presents critical pest management and pesticide education articles for Montana homeowners, pesticide applicators, farmers and ranchers. These articles are designed to deliver timely updates from an unbiased perspective that are specific to Montana. This is a cooperative effort between Montana State University pesticide education and integrated pest management programs.

In this Issue

- Crop Harvesting and Weed Management

- Sugarbeet Integrated Pest Management Impacts in Montana

- Regional Private Applicator Programs

- What’s That Grass Growing on the Other Side of the Fence?

- Ask the Expert

- Pest Management Toolkit

- Meet Your Specialist: Eva Grimme

- Acknowledgments

Crop Harvesting and Weed Management

by Fabian Menalled, MSU Crop Weeds Specialist, Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences

Figure 1: Wheat field. Photo courtesy of USDA-ARS.

Many times we think of crop harvesting and weed management as two independent tasks. Yet harvesting provides a great opportunity to improve weed management. First and foremost, while in the combine farmers have a unique opportunity to reflect on the season’s successes and failures. Systematically traveling across the fields provides a great chance to reflect on approaches for the next crop’s weed management program by carefully checking locations of which species thrived this year. The next step is to find out what went wrong and what can be improved. The following is a list of some of the many things farmers could think about at harvest.

Weeds Occur in Patches

In general, weeds are not distributed uniformly across fields but in patches of high densities. Several causes could be responsible for these patches. Is it possible that you have selected herbicide resistant weed biotypes? Did you get bad crop establishment during the summer that resulted in a less competitive canopy at the site of the weed patch? Is there any underlying nutrient or moisture characteristic at that site that could have resulted in an increased weed survivorship and growth? Carefully considering these and other potential mechanisms responsible for the success of the weed population you detect in a particular field can help adjust the management approach to prevent the growth of these patches.

Post-Harvest Weed Management

Weed species such as kochia are difficult to control once they have been cut by the combine because they drop their seeds in one spot. Because kochia seedlings can emerge at any time during the winter, they can produce dense clumps of seedlings which are very hard to control as their mass impedes effective herbicide coverage. Post-harvest treatments with glyphosate (Roundup and other generic names) and paraquat applied late August to early September when kochia plants are actively growing and have produced enough leaf tissue for herbicide absorption can help to substantially reduce seed production. However, post-harvest herbicide options should not be based or planned solely on the weed species currently in the field, but also take into account the spring planting intentions.

Impact of Harvesting on Weed Communities

Weed species are differently influenced by crop harvesting operations and their strength and selectivity depend on timing and technique. For example, repeated growing of the same crop harvested at similar times and by similar methods selects specific weed species. The timing of harvest and stubble height are decisive selective factors for which weed species will produce seeds, the amount of seeds being produced, as well as dispersal patterns. For example, high stubble can lead to higher seed production of species such as common mallow or prostrated knotweed. Variations in timing and methods of harvesting and diversified crop sequences can help avoid selecting for specific and difficult to manage weed species.

Figure 2: Barley harvest. Photo courtesy of USDA-ARS.

Managing Winter Annual Species

Winter annual species such as cheatgrass and jointed goatgrass germinate and emerge in late summer, become semi-dormant and overwinter, resume growth in early spring, and flower and complete their life cycle the following summer. Farmers increasing acreage of winter crops shouldn't be surprised that winter annual weeds become a widespread management issue. Managing winter annual weeds starts in fall when they are more susceptible to weed control practices and scouting for their presence can give a head start on management.

Harvest the Weediest Field Last and Carefully Clean the Combine

Leaving the worst fields for last is a simple approach to minimize the spread of weed seed and has been shown to be economically effective. Carefully cleaning equipment is another simple approach to minimize the transfer of weed seeds between fields. These simple steps can help farmers minimize the spread of weeds, including herbicide resistant biotypes.

Fall Is the Time to Manage Perennial Weeds

As fall temperatures cool, growers have an opportunity to manage perennial weeds.

Cooler temperatures trigger the movement of food reserves down to the root systems,

enhancing movement of herbicides to the plant’s root system and improving control.

However, farmers should be aware that perennial species vary in sensitivity to frost,

and the application window differs between species. For example, Canada thistle can

survive light frosts and is effectively controlled with relatively late fall herbicide

applications. Other perennial weeds such as hemp dogbane and common milkweed complete

their life cycles by late summer and do not tolerate frost well, so fall herbicide

applications should not be delayed when controlling these species. Finally, although

fall application will not guarantee excellent control of field bindweed, late control

practices can be effective, provided there is re-growth of this species.

These are just a few fall season considerations farmers can take into account to develop

effective integrated weed control programs.

Sugarbeet Integrated Pest Management Impacts in Montana

by Barry Jacobsen, Interim Department Head of Montana Agricultural Experiment Stations and Agricultural Research Centers, MSU Professor of Plant Pathology

Figure 3: Cercospora leaf spot early defoliation. Photo by Barry Jacobsen.

Sugarbeets are grown on 60,000-70,000 acres in Montana, with 35,000+ acres grown in the Sidney Sugars factory district and 30,000 acres in the Western Sugar Billings factory district. These two areas have somewhat different challenges. From 1990 to 2000 the key problem in the Sidney Sugars factory district was Cercospora leaf spot. Growers sprayed each acre four times per year with fungicides to control this disease.

Cercospora leaf spot reduced sugar production tonnage per acre by 10-12% and dramatically increased storage losses. In 1996 there was widespread resistance to the key benzimazole fungicides, which were commonly used to treat Cercospora leaf spot, and great concern about resistance to other fungicide alternatives. Something needed to be done.

Infection and sporulation by the Cercospora leaf spot pathogen is strongly affected by environmental conditions, and a weather-based prediction system borrowed from the Minnesota/North Dakota production area was adapted for Montana. Sugarbeet company field workers were trained in the use of the system and field monitoring techniques, and they communicated infection period information to growers. This resulted in better and more effective timing for the first fungicide application, and growers saved on the average $15-16 per acre (about one spray per year). In addition, new classes of fungicides were identified and labeled along with strong resistance management training of both growers and field workers. To date sugar beets have not lost another class of fungicides to resistant Cercospora isolates, while resistance to the QoI fungicides in Minnesota, North Dakota and Michigan have resulted in this class of fungicides being lost to growers in those states.

Historically sugarbeet varieties with resistance to Cercospora have also had very low yield potential. We began evaluating varieties with varying levels of resistance and demonstrated that varieties with partial resistance could be sprayed with fewer fungicide applications with no loss in yield compared to susceptible varieties sprayed with four fungicide applications. Based on this research and Extension education programs, Sidney Sugars reduced its variety requirements to a KWS rating of 5.3 or less. this was a significant change from no prior Cercsopora resistance requirement or varieties having KWS scores of 6-7. The KWS score is from 0 (immune) to 9 (highly susceptible). Today

most varieties have a KWS score between 4 and 5. This change plus the monitoring system has resulted in growers now using 1-2 applications of fungicide per year compared to the prior four times per year. This means a savings today of more than $40 per acre or $1.4 million per year and application of about 22,000 pounds of fungicide compared to 70,000 pounds without Integrated Pest Management (IPM). Other research has shown that this can be reduced further by utilization of an MSU developed biological control that will soon be labeled and marketed by CERTIS USA.

Figure 4: Close up of Cercospora leaf spot. Photo by Barry Jacobsen.

In the Western Sugar Billings factory district, challenges were Aphanomyces root rot, Fusarium yellows, sugarbeet root maggot and sugarbeet root aphid. The use of improved fungicide and insecticide seed treatments that address problems such as Aphanomyces root rot, Rhizoctonia damping-off and crown rot, curly top virus and sugarbeet root maggot have greatly reduced stand losses and greatly improved yield potential. Other major changes have been the widespread use of properly timed post-emergent fungicide treatments that control Rhizoctonia root and crown rot, plus required variety resistance to Fusarium yellows and sugarbeet root aphid. Together these changes have increased yields by more than 20% in the past 20 years. The Cercospora leaf spot disease is not as severe in the Billings factory district, and growers there have reduced fungicide applications by nearly 50%. IPM programs have had a dramatic impact on the profitability and sustainability of the sugarbeet industry in Montana.

Regional Private Applicator Programs

by Cecil Tharp, MSU Pesticide Education Specialist, Department of Animal and Range Sciences

Pesticide applicator training. Photo by Cecil Tharp.

Individuals applying pesticides on land that they own, rent or lease are increasingly concerned with the proper application of pesticides to minimize health concerns and environmental impacts. Applicators often have questions:

- Did I apply the proper amount of pesticide?

- Did I select the proper pesticide?

- What should I do if I have a pesticide spill?

- How do I protect myself and my family from pesticides?

- How can I minimize impacts to beneficial organisms while using pesticides?

These individuals may also find it difficult to manage some pests with only general use (over the counter) pesticides. To answer these questions and allow pesticide users access to a wider array of pesticides, the Montana State University (MSU) Pesticide Education Program (PEP) is sponsoring multiple regional initial training programs for individuals across Montana.

This statewide effort will assist pesticide users in understanding how to use pesticides effectively and safely, and will also license individuals as private pesticide applicators. A private applicator license allows the purchase of a wider range of pesticides (restricted use pesticides) when managing pests on land that an applicator owns, rents or leases. ˛is training won’t license individuals as commercial (for hire) or government (government or tribal in Montana. The MSU Pesticide Education Program is offering regional initial certification programs in Miles City, Bozeman, Billings and Kalispell during the winter and spring of 2015. These six-hour programs will license audience members as private pesticide applicators after taking an ungraded and interactive quiz at the end of the training. Trainings are also worth six private applicator recertification credits to individuals currently licensed as private applicators. Trainings will cover seven core areas including:

- Understanding the Private Applicator License

- Integrated Pest Management

- Reading and Understanding the Product Label

- Effective Calibration of Sprayers

- Environmental Fate and Movement of Pesticides

- Pesticide Laws and Compliance

- Pesticide Safety and Toxicity

By bringing in experts from the Montana Department of Agriculture, MSU Pesticide Education Program, MSU Extension and the MSU Integrated Pest Management programs, individuals should leave these trainings more prepared to make sound decisions regarding pesticides. Audience members should expect interactive calibration demonstrations using on-site spray equipment as well as interactive demonstrations of pesticide exposure and personal protective equipment. Presentations will also focus on many herbicide fate scenarios that impact Montanans including 1) non-target pesticide toxicity in homeowner gardens, 2) why over 70% of private applicators spray in high wind, 3) non-target damage from spraying in high wind and 4) how to avoid these growing threats.

Training costs vary from $10 to $25. There will be a $10 charge at the door for all audience members to cover beverages, snacks and travel costs. For private applicators seeking to obtain their license for the first time, there’s an additional $15 charge for extra training materials.

- Billings – February 25

- Miles City – February 24

- Bozeman – March 4

- Kalispell – March 26

Meeting locations within Kalispell, Bozeman, Miles City and Billings are still pending, but pre-registration is mandatory. Contact Cecil Tharp (MSU Pesticide Education Coordinator) for more information or to pre-register.

What’s That Grass Growing on the Other Side of the Fence?

by Jane Mangold, MSU Invasive Plant Specialist, Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences

Figure 6: Grasses are a ubiquitous feature of Montana’s landscape. Photo by Jane Mangold.

We often joke about the grass being greener on the other side of the fence. In reality, the grass may be greener on the other side of the fence, depending on the grass’ identity. Grass identification is not easy, though; many times the skills to do so are neglected because grass identification is so challenging. In addition many people assume that all grasses look alike and one grass species functions just like any other grass species. This article explains why grass identification is important, describes several key anatomical features to look at on a grass to help you with identification, and suggests some additional resources to make grass identification easier.

Over two-thirds of Montana is dominated by grasses, and over 230 grass species have been documented in Montana. Many people manage private or public land in Montana to promote healthy vegetation, and grasses are usually a large component of the plant community that managers are seeking, especially for livestock and wildlife forage. The species of grasses present in a rangeland plant community or crop field can be used as an indicator of overall health of the range or crop system. Some grasses are invasive (e.g. cheatgrass, Japanese brome, medusahead, smooth brome), so proper identification of them is critical to conserving our Montana grasslands. In regards to control of broadleaved noxious weeds, some commonly used herbicides can injure grasses, but injury can be species specific. In addition, an increase in grass production that often results from noxious weed control can also be species specific. Given these facts, knowing what grass species are growing in a plant community can inform land management decisions and help to predict the outcome of weed management activities.

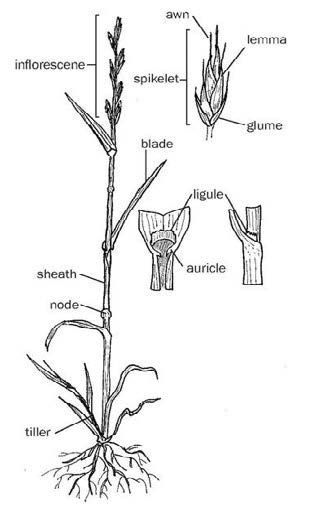

Figure 7: Grass with labeled anatomical features. Drawing from Grass Identification Basics (MT201402AG).

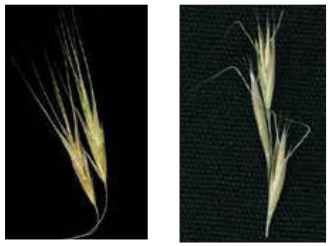

Figure 8: Awns on seeds of cheatgrass (left) and bent awns on seeds of ventenata (right).

Grass identification requires you to look at vegetative characteristics along with flowering or seed head features, all of which can be small and usually are not very showy. Many of the terms used to describe grass anatomy are different than those used for describing dicots (i.e. broad-leaved plants), which adds to the challenge. First, however, look at the overall appearance of the grass for a clue to its identity. If it’s growing in a clump of basal leaves and stems, then it’s a bunchgrass. Rhizomatous, or creeping grasses do not form clumps but instead have a spreading appearance. Some grasses are so strongly rhizatomous that they form a solid mat and are described as sodgrasses.

One of the more important areas to look at on a grass, especially when it is in the vegetative stage, is where the leaf blade arises from the stem. Here you can observe the sheath, which is the lower portion of the blade that wraps around the stem, the ligule, and the auricle (Figure 7).

The ligule is a thin, paper-like membrane or line of hairs on the inside of the leaf blade at the junction of the sheath and blade. Auricles are small outgrowths or ear-like lobes that occur on either side of the leaf sheath-blade junction. Characteristics of the sheath, ligule, and auricles give clues to species identity.

Once the grass inflorescence (flower/seed head) is present, identification becomes easier. The shape of the inflorescence will either be spike-like, tightly branched, or loosely branched. Timothy is a good example of a spike inflorescence.

The needlegrasses and fescues have tightly branched inflorescence, and switchgrass is an example of a grass with a loosely branched inflorescence. There are many features of the inflorescence that are used for identification, but probably one of the more conspicuous is the awn. Awns are slender bristles attached to some portion of the floret. These are the somewhat pesky appendances on a seed that stick to animals, socks and shoes (e.g.cheatgrass or needle-and-thread grass). Awns can be absent, short, or long. Some species have distinctly bent awns, which add even further information for identification (Figure 8).

Grass identification is challenging, but once you get the hang of it, it can be fun and will certainly deepen your appreciation for grass diversity. This article has only touched the surface of grass identification, but several tools exist to provide further help:

Grass Identification Basics (MSU Extension MontGuide MT201402AG) elaborates on many of the thoughts presented in this article.

Montana State University teamed with High Country Apps to develop the Montana Grasses mobile app which allows you to browse through 105 of the most common grasses in Montana as well as search by characteristics. The app is available for Apple and Android devices on High Country Apps and costs $4.99.

Other useful resources include:

- Range Plants of Montana (MSU Extension, EB0122)

- Forage and Reclamation Grasses of the Northern Great Plains and Rocky Mountains (Majerus, NRCS Bridger Plant Materials Center)

- Manual of Montana Vascular Plants (Lesica, Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Fort Worth, TX).

Ask the Expert

Extension IPM specialists provide answers to reader questions.

Question: Do I need a pesticide license to apply pesticides around my home?

Cecil Tharp says: No. Individuals don’t need a private pesticide license if using general use pesticides on land that they own, rent or lease, however individuals using restricted use pesticide products need a pesticide license. Restricted use pesticide products are pesticide products that present a higher risk to human health or the environment. These products often have higher toxicity and/or move more easily in the environment causing non-target damage. Restricted use products will contain the statement ‘Restricted Use’ on the first page of the pesticide product label. Individuals applying pesticides for hire or on public lands must always have a pesticide license, regardless of the pesticide used.

Question: I turned over some of my alfalfa bales and noticed these worms underneath the bales, on the cement floor. What are they, and how can I get rid of them?

Kevin Wanner says: These larvae are a type of pyralid moth. There are several pyralid species that feed during the larval stages on stored hay, as well as stored grains and decaying manure. The likely culprit in your situation is Aglossa caprealis, which is known by several common names (fungus moth, murky meal moth, small tabby moth). A. caprealis is not a problem unless the hay is damp – either because it was not well dried before baling, or due to wet storage conditions. Even hay that seems sufficiently dry can accumulate mold once in storage, and this is why some producers wait several weeks after baling before storing bales in the barn. For this year, discard any damp, moldy bales in your barn, and check carefully for moisture sources. If there is a practical way to improve ventilation and to raise bales up off the floor (wood pallets, railroad ties), this will aid air circulation and discourage further infestation. A. cerealis is an introduced European species that occurs regularly in the northern U.S. Rocky Mountains region. In hay, the larvae are found feeding from silk tubes.

Question: What are the risks of the next ‘new’ technology for managing weeds?

Fabian Menalled says: The USDA is currently reviewing several crop varieties which can be sprayed with group 4 herbicides (HG 4, growth regulators) without damage, thus allowing the herbicide to be used to manage weeds with little to no negative impact to the crop. Specifically, Monsanto is developing a soybean variety resistant to dicamba, and Dow AgroSciences is developing corn, soybean and cotton varieties resistant to 2,4-D. Whereas it is very possible that the adoption of these crops in Montana will be rather low, a large demand is anticipated in other regions of the country largely due to the growing problem of evolved herbicide resistance, including resistance to glyphosate (Roundup and other generic products) and multiple herbicide resistance. Compared to other herbicide groups, the probability of resistance to group 4 herbicides is considered to be low. However, this was also the case with glyphosate (HG 9). Furthermore, kochia populations with evolved resistance to growth regulators were detected in Montana more than 20 years ago. Thus, unless farmers adopt a proactive diversified management approach to minimize the selection of herbicide resistance, it is very possible that we will see a nationwide increase in resistance to growth regulators. Unfortunately, weeds seeds of many species are highly mobile, and resistance could arrive in Montana soon after. Bob Hatzler, a weed scientist at Iowa State University, provides a comprehensive review about this issue in Group 4 (Growth regulator herbicides) Resistance in Weeds.

Question: Is it possible for spotted knapweed biological control agents to show up in an infestation even though no biocontrol releases have been done in the area?

Jane Mangold says: Yes, it is possible, especially for those agents that readily fly like the Urophora fly or the Agapeta moth. Dispersal of those insects that don’t fly at all or don’t fly very well, like Cyphocleonus and Larinus weevils, is typically more limited but still possible even without scheduled releases. We recently completed a study where we surveyed for biocontrol agents at about 30 sites in western Montana during different seasons over the course of two years. In that study Urophora affinis was found at 73-100% of the sites and Larinus spp. was found at 18-82% of the sites (range due to season of sampling). One of the benefits of biological control is the natural dispersal of the insects on their own accord with sometimes very little input from us.

Pest Management Toolkit

From Fabian Menalled

iWheat, an Online Source of Information for Wheat Producers

This web site provides a comprehensive review of more than 20 years of research, Extension and education programs on Integrated Pest Management in wheat. The iWheat site provides news and progress on desktop modules, smartphone apps, and other platforms as soon as information is available. Farmers can find factsheets, articles, and videos on pest detection and evaluation, farm and field level pest management, and reduced risk pest management approaches. You can become a member of iWheat or simply search for information by visiting iwheat.org.

From Kevin Wanner

The 2015 Crop and Pest Management School

The 2015 Crop and Pest Management School will be held on the MSU campus January 5-7. The 2.5 day workshop will focus on small grains topics, with guest speakers and MSU staff covering topics in weed, disease, insect and nutrient management as well as wheat breeding. Credits for crop consulting and pesticide application will be available. Watch for the schedule and registration information this fall.

Wheat Midge Emergence

Check out this cool website! It was initiated by Bob Stougaard and Brooke Bohannon (Northwestern Ag Research Center) and developed by John Sully (Software Engineer in the MSU College of Agriculture) to track wheat midge emergence.

From Cecil Tharp

IPM Technologies Reference Sheet

It can be difficult to select useful technologies that are easy to use yet effective when managing pests. Use the IPM Technologies Reference Sheet created by many MSU Integrated Pest Management professionals to select tools for tank mixing, selecting nozzles, calibrating sprayers or identifying pests. This sheet contains a variety of mobile apps, websites and other technologies that are readily available and often free to users. This can be accessed online at [expired link, go to the Pesticide Education Program website for current information].

Pest Management Tour

Livingston, Belgrade, Whitehall, Philipsburg, Helmville, Butte, Dillon and Townsend. Oct. 6 through 10. This is worth six private applicator recertification credits. For more information or to pre-register see the complete agenda at pesticides.montana.edu by selecting ‘private applicator program’ and selecting ‘Montana PAT Region 2.’ Contact Cecil Tharp at (406) 994-5067 for more information.

Initial Private Applicator Training

Lame Deer, Nov. 13, 2014; Miles City, Feb. 24, 2015; Billings, Feb. 25; Bozeman, March 4; and Kalispell, March 26. This program can license individuals to apply restricted use pesticides on land that they own, rent or lease. It is also worth six private recertification credits to licensed private applicators. For more information or to pre-register contact Cecil Tharp at (406)994-5067. The complete agenda is viewable online at [expired link, go to the Pesticide Education Program website for current information].

From Jane Mangold

New Montana State University Extension Publications

Early Detection and Rapid Response (EDRR) to New Plant Invaders covers key concepts of EDRR and suggests three easy steps one can take to contribute to statewide EDRR efforts. Available at the Montana State University Extension store, Publication 4604.

Watch out for Medusahead bulletin [no longer available] from Montana State University Extension store, Publication EB0218.

New Website from the Montana Noxious Weed Education Campaign

Check out weedawareness.org, the updated and searchable website from the Montana Noxious Weed Education Campaign.

Montana Weed Control Association Annual Conference

January 14-15, 2015, at the Heritage Inn in Great Falls. Visit mtweed.org for more information.

Meet Your Specialist

Eva Grimme, Plant Diagnostician, Schutter Diagnostic Lab

Tell us about your background. Where and when did you receive degrees?

Tell us about your background. Where and when did you receive degrees?I started my career as an apprentice in a two-year program to become a professional gardener. I received my degree as a horticulture engineer in 2001 from the University of Applied Sciences Weihenstephan-Triesdorf, Germany. My master’s degree in Plant Sciences (2004) and my doctorate in Plant Pathology (2008) were both from Montana State University, Bozeman, with my advisor, Dr. Barry Jacobsen.

What is your field of interest?

My work and research has focused on the biological control of soil-borne pathogens. Additional areas of interest include integrated pest management and horticulture and mycorrhizal ecosystems.

When did you arrive in Bozeman?

I was very fortunate to be chosen for an internship at MSU in 1999. When I arrived in Bozeman, I fell in love with the surroundings. Therefore, starting my new position in May 2014 as plant disease diagnostician in the Schutter Diagnostic Lab was more like a coming home experience.

Where are you from originally?

I am originally from the city of Fulda. This wonderful city is in the county of “Hessia” in Germany.

Where have you worked in the past?

During my studies in Germany, I worked as a professional gardener for display gardens at the University of Applied Sciences. As a graduate research assistant, I worked on multiple plant pathology projects. Following graduate school, I worked for Dr. Cathy Cripps at MSU as a postdoc and that experience greatly enhanced my understanding of mycorrhizal fungi. Prior to starting my current position, I worked for Dr. Nora Olsen at the University of Idaho, Research and Extension Center in Kimberly, Idaho, for five years. There I focused on research to control potato tuber diseases under storage conditions. Furthermore, I had the opportunity to gain valuable insights into the duties of an Extension professional.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

In my free time, I enjoy exploring Bozeman and the surrounding area. I like to wind down with reading or gardening. Splitting wood will probably be added to the list for this winter (I don’t know if that qualifies as a hobby).

What are some of your current projects?

Currently, my focus is diagnosing plant diseases in the Schutter Diagnostic Laboratory. It is challenging and rewarding to do necessary “detective” work to discover what the problem is with samples that are brought or shipped in and then give recommendations. The variety of incoming plants, from tree to aquatic plant samples, in addition to interaction with clients, challenges me every day in a positive way.

How can farmers use your research to their benefit?

For the professional producers and hobby horticulturists who bring in diseased samples, a correct diagnosis is essential. I am privileged to work with experts in fields of entomology, plant identification, and horticulture, thus making it possible to provide clients with correct information and support the implementation of integrated pest management. We strive to save affected plants and reduce application of unnecessary treatments; we are always looking for effective treatment alternatives.

What projects would you like to focus on in the future?

I would like to work on resistance testing with Ascochyta as well as soil-borne pathogens in collaboration with a grad student. I’m looking forward to working with all of you. Please stop by the Schutter Lab next time you’re at MSU.

Acknowledgments

Do You Have a Question or Comment Regarding the Montana IPM Bulletin?

Send inquiries and suggestions to:

Cecil Tharp

Pesticide Education Specialist

P.O. Box 172900

Montana State University

Bozeman, MT 59717-00

Phone: (406) 994-5067

Fax: (406) 994-5589

Email: [email protected]

Web: pesticides.montana.edu

Jane Mangold

Invasive Plant Specialist

P.O. Box 173120

Montana State University

Bozeman, MT 59717-3120

Phone: (406) 994-5513

Fax: (406) 994-3933

Email: [email protected]

Web: landresources.montana.edu

Noelle Orloff

Associate Extension Specialist

P.O. Box 173120

Montana State University

Bozeman, MT 59717-3120

Phone: (406) 994-6297

Fax: (406) 994-3933

Email: [email protected]

Web: diagnostics.montana.edu

Common chemical and trade names are used in this publication for clarity by the reader. Inclusion of a common chemical or trade name does not imply endorsement of that particular product or brand of herbicide. Recommendations are not meant to replace those provided in the label. Consult the label prior to any application.

Original Fall 2014 PDF (750KB)